Writers look for nuance in multilingual writing.

4/8/2025 • Louise Farr

Deli Boys Writers Bond Over Backgrounds

The Onyx series’ multi-cultural writers’ room brings South Asian characters to the fore.

As Celine Song was writing her screenplay for the bilingual film Past Lives, a fictionalized but personal story of separated childhood sweethearts, she wrote some scenes in Korean, a language in which she hadn’t written since leaving Seoul for Canada at age 12. Other scenes she wrote in English, with each language emerging spontaneously as she wrote.

“It’s actually quite chaotic. There’s no real rhyme or reason except for maybe poetic rhyme or reason: Well, the Korean version of this line is going to be better than the English version,” Song says about her 2024 Writers Guild Award-nominated script. “When I’m translating those two languages, I’m also thinking about what actually conveys the meaning or the poetry of that language.”

Themes of loss, distance, and miscommunication are central to Past Lives—and those themes become heightened when bilingualism, and language itself, are part of the story.

“The film is being written in a way where the actual mechanic reality of it, which is that it is written in two languages, is connected to the heart of the film,” says Song, who in the beginning wondered if anyone would be interested in her bilingual film at all.

She was writing before the 2019 film Parasite, written by Bong Joon Ho and Han Jin-won, won an Oscar, and before the pandemic, when audiences trapped at home with Netflix began to explore a wider range of foreign films and television. A lightbulb went off then: If the underlying material was compelling enough, subtitles were not only acceptable, they helped open up exciting new worlds. Now, with that barrier broken, when we flip on a mainstream American TV show or movie, we’re more likely to see characters speak in their native languages, with subtitles.

But early in pitching her film, Song received notes that asked if the film really had to be subtitled.

“It’s a great way to weed out people who are not good partners,” she says. “How lucky that I found out right away.”

Of course, her film had to be subtitled. But, like other writers Written by spoke to about the challenges of bilingual writing, Song didn’t aim for mere literal translation when writing subtitles. Instead, within each language, she sought cultural and emotional nuance.

“It’s still a movie,” she says. “If you’re only concerned about doing something that’s ‘authentic,’ then it’s going to fall apart as art.”

Context Counts

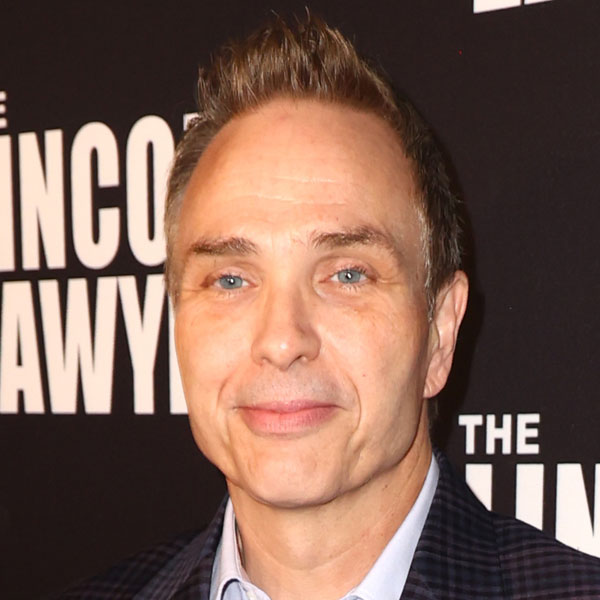

Mickey Haller, protagonist of Netflix’s series The Lincoln Lawyer, grew up in Mexico. Sprinkling his dialogue with Spanish words or phrases lends truth not only to Haller’s character, but to heavily Latine Los Angeles, where the show is set.

How much Spanish to include depends on the context of a scene, says co-showrunner Dailyn Rodriguez. Scripts are written in English, then Rodriguez, born to Cuban parents, translates any relevant dialogue into Spanish.

In season 2, episodes with Haller’s mother were written 95 percent in Spanish. In season 3’s fifth episode, written by Ryan Hoang Williams, Haller approaches an imprisoned cartel boss, offering to help expose that this villain has been framed by a crooked cop. At first the room—which has three Spanish-speaking writers, including Rodriguez—considered writing it all in Spanish, since both actors spoke the language.

“It was such a very long scene and had such important information that we decided instead to write the scene in English and then just have certain emotional turns in the scene being in Spanish,” says Rodriguez, a WGAW Board member whose first language is Spanish. “When I go in and out of speaking Spanish and English with, let's say, my sister, I usually revert to Spanish when it's something emotional, or a piece of slang, or a way that something sounds better in Spanish than English.”

The writers follow that pattern for Mickey Haller.

“Figuring out what those moments are in the scene, that's the difficulty,” Rodriguez says.

Also, the type of Spanish needs to be specific, so the show’s Mexican star, Manuel Garcia-Rulfo, checks Rodriguez’s translation. Specificity doesn’t include translating idioms, according to Ted Humphrey, who developed the series based on Michael Connelly’s novels.

I feel like the more specific you can be, the more universal something becomes.

- Austin Winsberg

A literal translation of some Mexican slang, Humphrey says, “would sound like something that doesn't make any sense. So we don’t translate that literally. We translate it figuratively.”

Don’t Make Me Laugh

The Apple TV+ series Acapulco takes place over decades in a hilariously over-the-top, glamorous Mexican resort. Early in talks with the network, says Austin Winsberg, who created the bilingual comedy with Eduardo Cisneros and Jason Shuman, the emphasis was on authenticity. Staff at an international hotel would necessarily be bilingual, so the creators developed rules: if they were by the pool, their boss would want them to speak English.

“But then, if the characters were in the break room, or if they were home with their family, or if they were somewhere where it would be authentic and natural for them to be speaking to each other in Spanish as their first language, that's what we did,” Winsberg says.

Translating jokes has perhaps become the trickiest issue. The position where the operative word of a joke lands may change in translation. In subtitles that can make a joke fall flat.

“We’ll come up with a joke in the room. We’ll love it. It’ll kill. Every single writer in the room will laugh,” says staff writer Bernardo Cubria. “Then we realize, Oh, the scene’s going to be in Spanish. Mexicans and Americans have very different senses of humor. And so then we change the joke.”

One such joke referenced Molly Ringwald’s bangs, until someone mentioned that a blue-collar family in 1986 Acapulco would hardly be thinking about Molly Ringwald, let alone her hairstyle. They cut the joke.

“I feel like the more specific you can be, the more universal something becomes,” says Winsberg, who mentions a scene in which a mother and grandmother become competitive over cooking for a posada party. Cubria suggested romeritos as the divisive dish, a mole with greens that some people find disgusting and others love, but everyone Mexican finds funny. “It's about what's the story point,” Winsberg continues. “You add in the specific, and then it makes it that much richer.”

As the bilingual Cubria writes, he hears the characters in his head in Spanish. “I’ll write scenes sometimes in English, sometimes in Spanish when I’m getting it out,” he says, but he simultaneously translates from Spanish to English, because he wants to know instantly if something will work in both languages. Ultimately, he shares an English document with the room, then story editor Ilse Apellaniz, who Zooms into the room from Mexico City, translates.

“She really is so good at getting the emotional and the funny of all of our scripts into both languages,” says Cubria.

Tone Poem

When Lulu Wang took on an adaptation of Janice Y.K. Lee’s novel The Expatriates for HBO’s six-part series The Expats, she didn’t expect to include Mandarin, Cantonese, Punjabi, Korean, and Tagalog, as well as the English in which Lee wrote exclusively. Those other languages emerged as Wang, working with her all-female writers’ room, expanded the stories of three key women and their foreign helpers from Lee’s book. By changing the nationalities and language of some of her leading characters, and expanding the Filipina helpers’ roles, Wang sought to broaden the conventional vision of expatriates as white people from America or other western countries, and the image of Hong Kong itself.

“I always like to challenge what I think people are expecting,” says Wang, who speaks Mandarin as well as English.

If Celine Song looked for poetry in language as she translated from Korean to English and vice versa, Wang immersed herself in the languages she didn’t know. Like Song, she was not interested in literal meaning.

A classically trained pianist, she would hear a rhythm, tone, and energy in everyday speech that would convey, even though written in English, a sense of the language to whoever would be translating.

With translators and language consultants in rehearsal and on set, she also gave actors permission to speak up if lines didn’t feel authentic.

“It’s a lot of debating, of them doing it and me saying, ‘Does that sound right?’ Kind of workshopping it with other people and relying on them to tell me,” she says.

This multicultural and multilingual approach to story stems from her own inquisitive nature, Wang explains. She also feels a sense of responsibility to the broader culture that may originate from being an Asian woman, and an immigrant herself, who left Beijing for Miami with her parents at age six.

“I follow my curiosity towards cultures, languages, that we don’t often hear that might just make the story more interesting,” Wang says. “Now there’s more representation, so that all of the responsibility doesn’t rely on one particular film, because no film or TV show can represent an entire group of people. We’re always going to leave something out, or it’s always going to be oversimplified in some way, because you can’t be comprehensive. So I just hope to contribute to a greater narrative in which there are more stories about all kinds of people.”