In honor of Women’s History Month, a look at the early days of the WGAW Women’s Committee.

12/5/2025 • Evan Henerson

Have a Wonderful Watch Party…and Bring a Toy!

Member holiday party to include a screening of It’s a Wonderful Life and a toy drive.

In honor of Women’s History Month, a look at the early days of the WGAW Women’s Committee.

In 1971, a young screenwriter named Diana Gould, inspired by the nascent women’s liberation movement, approached the WGAW Board to request the formation of a group for women writers. Many would consider her request unusual because it would exclude a majority of the membership from participating, given that women comprised only about 10% of the membership (in 1974, the committee voted to allow men to join). As Gould later recalled in a 1978 oral history interview, some of the Board also worried that allowing a women’s group would lead to other groups demanding their own committees.

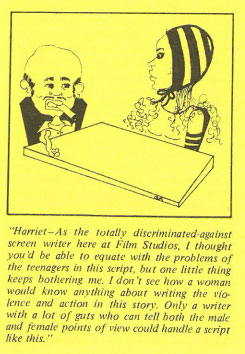

Nonetheless, the Board approved Gould’s request, a mailing went out, and 35 women showed up for the first meeting. They traded stories of subtle and overt gender discrimination: being the only woman in a room; sitting through meetings with sexual innuendo; not being submitted for a project by an agent because it was not a “female project”; and producers who explicitly said they would not hire women. Working in isolation, these women had probably never even seen each other, let alone participated in a forum for discussing common problems. Once women were given a space within the Guild, they realized they not only faced shared challenges in being taken seriously as professionals, but in getting into the room in the first place. When introducing the committee to members Gould noted that “women everywhere were asking what problems they had in common and what, together, they can do to solve them.” Their first step would be to raise consciousness among writers and the broader industry of the sexism they faced.

The committee went to WGAW Newsletter editor Allen Rivkin to create an issue profiling female writers and delving into topics related to women’s employment. The issue was published in November 1971. Aside from updates about Guild business and regular columns, the entire 22-page issue of the newsletter was devoted to women and written by women. There were profiles of Carole Eastman, Ida Lupino, Gloria Katz, and others. Two Black members, Jeanne A. Taylor and Eunice Braggs, wrote about what it meant to be Black writing “white stories” and “white characters.” The goals for the Women’s Committee, later renamed the Committee of Women Writers, were outlined. One piece speculated whether agents’ lack of imagination was the reason women weren’t being submitted for work. Another piece invited all members to attend the first workshop on offer from the committee, entitled “How to Sell a Story” and conducted by TV writers Elinor and Stephen L. Karpf.

The time was ripe for women in the industry to speak out and be heard. Shortly after the WGAW Women’s Committee was formed, the Screen Actors Guild created a women’s committee, and the two worked together toward mutual goals and networking for the first few years. Women in Film was founded by Hollywood Reporter publisher and editor Tichi Wilkerson Kassel in 1973. AFI’s Directing Workshop for Women was launched in 1974. The DGA Women’s Steering Committee was founded in 1979, and in 1983, committee members backed by the DGA brought a class action lawsuit against Warner Bros. and Columbia Pictures, alleging discrimination in their hiring of women and people of color (which was eventually dropped on a technicality).

In a union of writers, words are key. But numbers can tell a story, too. So, in 1973, the Women’s Committee set out to find empirical evidence that they were not being hired at the same rate as men. With staff support, committee members Joyce Perry, Noreen Stone, Jean Rouverol Butler, and others analyzed data collected by the Guild on series credits. They found that, though women comprised 13% of Guild membership at the time, they had only received 6.5% of teleplay writing and story credits on primetime TV shows. Only 1.5% of aired pilots were written by women. (At the time, data on feature credits was less reliable.) The report was meant for internal use, but Perry was compelled to go public and share it with her friend Sue Cameron, a columnist for the Hollywood Reporter. Cameron published the full report on November 27, 1973. It was the first report on employment discrimination by a Hollywood talent guild, and the industry took notice.

The following spring, Executive Director Michael Franklin shared the statistics in a letter to 850 signatory companies and asked producers to examine their own hiring practices and biases. The data and his questions to signatories were reprinted in the June 1974 issue of the WGAW Newsletter for the membership to see. One question simply asked, “Have you ever employed a woman as a writer? If not, why?” Another asked, “Do you believe that men write better than women? If so, do you have solid evidence to support that belief?” And yet another asked, “Is it possible that you have not hired a woman writer to write stories about men because you think women don’t know how to write about men? Do you feel the same about hiring men to write women characters and stories about women?”

In November of that year, the committee followed up with a second analysis of writing credits for primetime television shows on the three major networks, from October 1973 to September 1974. Credits for women in primetime TV had increased slightly to an average of 9.1% of all credits: 10.8% for ABC shows, 8.4% for CBS shows, and 8.2% for NBC shows. Furthermore, they found that out of 106 production companies, 61 had recorded no writing credits for women at all.

As the authors of the November report, Stone, Perry, and Howard Rodman Sr. wrote, “The relative invisibility of women writers becomes a self-perpetuating cycle. Producers confuse absence with lack of merit. Then agents find it easier to sell men writers. Then there are less women writers and that becomes the self-serving proof that women don’t write as well.”

The report had created a stir, and subsequent efforts were made to change course. Article 38 of the MBA calls for non-discrimination in hiring. Affirmative action plans were put in place in the late 1970s and 1980s, created to offer training and opportunities rather than direct employment. In the ensuing years, the Women’s Committee focused on networking and education to increase women’s knowledge of the craft and access to the marketplace. Members wrote a column in the newsletter periodically to keep shining a light on the sexism they faced, and they continued to write reports. In 1986, a staff person was hired to coordinate the non-discrimination programs under Article 38.

By the 1980s, women’s TV employment had increased incrementally, and features became a topic of research as well. In its 1984 report, the committee revealed that women accounted for 17% of primetime TV writing credits and 14% of feature writing credits. Women had created 13% of half-hour shows and 7.5% of hourlong shows, though female creator credits were often shared with male writing partners. Notably, the report called out shows by name that hadn’t given writing assignments to women on staff or didn’t staff women at all, including several shows created by women.

The same year, the committee lobbied the Board to hire social scientists to do a thorough analysis of Guild employment statistics. There had been discussions within the committee about appealing to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission for stronger action against discriminatory hiring practices, which they reasoned would require more in-depth proof of a pattern. The social scientists would also gather data on writers of color and older writers for what would become the first Hollywood Writers Report. Released in 1987, the report was prepared by two sociologists from UCSB—William and Denise Bielby—who focused on employment discrimination and the media industry. As reported, women made up about 20% of Guild membership and averaged about 22% of TV employment (across primetime, daytime, and children’s programming) and 16% of film employment. Earnings data showed that women earned 60 to 70 cents on the dollar compared to white men.

The numbers have moved steadily over the decades, and TV has consistently been the site of the greatest progress. According to the 2020 WGAW Inclusion Report, women accounted for 27% of features employment and 44% of TV employment in 2019.

Betty Ulius, one of the original Women’s Committee members, reflected in her 1978 oral history that one of the most lasting effects of the early work of the committee was to make the Guild feel less closed off, and create opportunities for more members to get involved. As expected, other groups did demand their own space within the Guild. The Committee of Black Writers was formed in 1975. The Latino Writers Committee, recently renamed the Latinx Writers Committee, was formed in 1977. Also in 1977, the Guild formed the Committee on Ethnic Minorities, which for several years served as an umbrella group for Black, Latino, Asian, and Native American writers. The Committee on Older Writers, now the Career Longevity Committee, began in 1980 and the Committee of Writers Concerned About Issues of Disabilities, precursor to the Disabled Writers Committee, was formed in 1982. (Four additional committees for underrepresented writers were formed in the 2000s: the Gay and Lesbian Writers Committee, now the LGBTQ+ Writers Committee, in 2002; the Asian American Writers Committee, also in 2002; the American Indian Writers Committee, now the Native American & Indigenous Writers Committee, in 2008; and the Middle Eastern Writers Committee, in 2020.) Each seized the political opportunities created by broader social movements to find power in numbers, and not just statistics. Four decades later, they must still continue to advocate for equity.

Sources

Gould, Diana. Interview for Writers Guild Oral History Project, August 22, 1978. Writers Guild Foundation.

Gould, Diana. "Raison d'etre for the Women's Group Meets.” WGAW Newsletter, Nov. 1971, 1,16-17.

Ulius, Betty. Interview for Writers Guild Oral History Project, April 12, 1978. Writers Guild Foundation.

Butler, Jean Rouverol. Interview for Writers Guild History Project, July 31, 1978. Writers Build Foundation.

Banks, Miranda. The Writers: A History of American Screenwriters and Their Guild. Rutgers University Press, 2015.

Gregory, Mollie. Women Who Run the Show: How a Brilliant and Creative New Generation of Women Stormed Hollywood. St. Martin’s Press, 2002.

Smukler, Maya Montanez. Liberating Hollywood: Women Directors & the Feminist Reform of 1970s American Cinema. Rutgers University Press, 2019.

This article was originally published in the March 26, 2021 issue of the WGAW Connect newsletter.